INDIAN ART of the United States [SOLD]

Forward to Friend

Forward to Friend

- Subject: Native American Art

- Item # C3516R

- Date Published: 1941, Second Edition

- Size: Hardback with slipcover, 224 pages, 208 plates (8 in full color) SOLD

INDIAN ART of the United States [Hardcover]

By Frederic H. Douglas and Rene D’Harnoncourt

Condition: very good condition

Published by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1941

Distributed by Simon and Schuster, New York

Hardback with slipcover, 224 pages, 208 plates (8 in full color). Nine thousand five hundred copies of this second edition have been printed in April 1948 for the Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art by the Plantin Press, New York

From the Jacket

“This is the most complete work on the art of the United States Indian ever published—the portrait of a civilization.

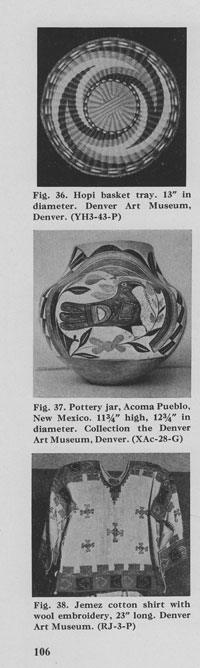

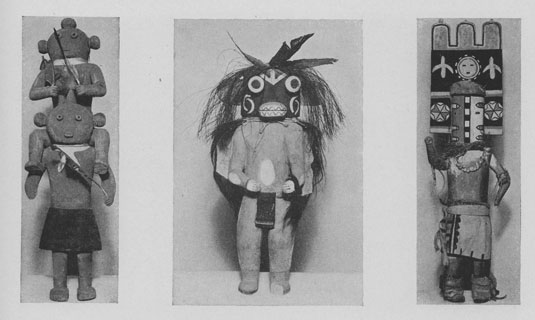

“Mr. Douglas and Mr. D’Harnoncourt, acknowledged authorities in their field, have combined skillful research with a lively sense of esthetic excellence in selecting and revealing the astonishing, little-known art of our predecessors in this country. For more than fifteen hundred years this race of artists, working in various media, has maintained a continuous record of high artistic achievement. Proceeding from mysterious objects of dateless antiquity to contemporary work as modern in spirit as Klee or Picasso, the authors discuss sculpture, pottery, weaving, embroidery, jewelry, pipes and toys, weapons, pictographs, murals and sand paintings. The range of materials is extraordinary, among them ivory, silver, copper, mica, shell, quills, hide, bone, fur, claws and hair.

“Mr. Douglas and Mr. D’Harnoncourt, acknowledged authorities in their field, have combined skillful research with a lively sense of esthetic excellence in selecting and revealing the astonishing, little-known art of our predecessors in this country. For more than fifteen hundred years this race of artists, working in various media, has maintained a continuous record of high artistic achievement. Proceeding from mysterious objects of dateless antiquity to contemporary work as modern in spirit as Klee or Picasso, the authors discuss sculpture, pottery, weaving, embroidery, jewelry, pipes and toys, weapons, pictographs, murals and sand paintings. The range of materials is extraordinary, among them ivory, silver, copper, mica, shell, quills, hide, bone, fur, claws and hair.

“A special section of eight plates is devoted to color in Indian art. The many black and white photographs are particularly fine, and the running text, as usual in Museum of Modern Art publications, provides a primer for the layman as well as an authoritative handbook for the scholar.”

From the Introduction:

TRIBAL TRADITIONS AND PROGRESS

For centuries the white man has taken advantage of the practical contributions made by the American Indian to civilization. Corn, one of the food staples most widely used today, was developed thousands of years ago through the diligence and patience of Indian agriculturists. Tomatoes, squash, potatoes and tobacco were cultivated on this continent long before the white man's arrival. In fact, the white invader was only too glad to learn from the Indian how to utilize the material resources of this country and adopted many of the native methods for his own use.

In spite of this ready recognition of the material achievements of the various Indian tribes, we have hardly ever stopped to ask what values there may be in Indian thought and art. An almost childish fascination with our own mechanical advancement has made us scorn the cultural achievements of all people who seem unable or unwilling to follow our rapid strides in the direction of what we believe to be the only worth-while form of progress.

For four centuries the Indians of the United States were exposed to the onslaught of the white invader, and military conquest was followed everywhere by civilian domination. As war never encourages objective appreciation of cultural values in the enemy camp, it is not surprising that in the days of the Indian wars tribal traditions were regarded as contemptibly backward. But it is deplorable that the advent of civilian domination added actual suppression to scorn. This destructive attitude of the civil authorities was rarely due to hostility. In many cases it was simply the result of their complete lack of understanding of Indian life, and sometimes it was even a manifestation of misguided good will. Indian tradition was seen as an obstacle to progress and every available means was employed to destroy it thoroughly and forever. Dances and ceremonials were outlawed, arts and crafts were decried as shameful survivals of a barbaric age and even the use of Indian languages was prohibited in many schools.

Only in recent years has it been realized that such a policy was not merely a violation of intrinsic human rights but was actually destroying values which could never be replaced, values so deeply rooted in tribal life that they are a source of strength for future generations. In recognition of these facts, the present administration is now cooperating with the various tribes in their efforts to preserve and develop those spiritual and artistic values in Indian tradition that the tribes consider essential. At the same time, the administration makes every effort to help them realize their desire to adopt from the white man such achievements as will make it possible for them to live successfully in a modern age. This attitude led to the promulgation of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which created a legal basis for the rehabilitation of Indian economic and cultural life. By this Act we are taking into consideration for the first time tile validity of Indian tradition as well as the need for progress.

It is impossible to generalize on the present status of tribal tradition in the various groups. Some of them are still guided by tradition in all their activities and regard it as the basis of their entire economic, social and ceremonial life. Others have adopted some of the white man's ways, and some preserve tradition only in such subtle aspects of their culture that its existence is often imperceptible to the casual observer. It is also frequently true that factions within a tribe represent various attitudes ranging from strict adherence to open defiance of it. However, it must be said that Indian tradition still permeates in varying degrees every tribal unit that has not been completely absorbed by its white neighbors.

The survival of tribal cultures through generations of persecution and suppression is in itself a testimony to their strength and vitality. It is natural that a new appreciation of these values by the authorities and by part of the American public is now bringing to light in many places traditional customs and traditional thinking that have lived for years carefully shielded from unsympathetic eyes.

But our new willingness to recognize the value of Indian traditional achievement is unfortunately sometimes fostered by sentimentality rather than by true appreciation. There are people who have created for themselves a romantic picture of a glorious past that is often far from accurate. They wish to see the living Indian return to an age that has long since passed and they resent any change in his art. But these people forget that any culture that is satisfied to copy the life of former generations has given up hope as well as life itself. The fact that we think of Navaho silversmithing as a typical Indian art and of the horsemanship of the Plains tribes as a typical Indian characteristic proves sufficiently that those tribes were strong enough to make such foreign contributions entirely their own by adapting them to the pattern of their own traditions. Why should it be wrong for the Indian people of today to do what they have done with great success in the past? Invention or adaptation of new forms does not necessarily mean repudiation of tradition but is often a source of its enrichment.

To rob a people of tradition is to rob it of inborn strength and identity. To rob a people of opportunity to grow through invention or through acquisition of values from other races is to rob it of its future.

This publication, as well as the exhibition upon which it is based, aims to show that the Indian artist of today, drawing on the strength of his tribal tradition and utilizing the resources of the present, offers a contribution that should become an important factor in building the America of the future.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Tribal Traditions and Progress

Indian Art

Indian Origins and History

Color in Indian Art

Prehistoric Art

The Carvers of the Far West

The Carvers of the Northwest Coast

The Engravers of the Arctic

The Sculptors of the East

The Painters of the Southwest

Pictographs

Living Traditions

Introduction

The Pueblo Cornplanters

The Navaho Shepherds

The Apache Mountain People

The Desert Dwellers of the Southwest

The Seed Gatherers of the Far West

The Hunters of the Plains

The Woodsmen of the East

The Fishermen of the Northwest Coast

The Eskimo Hunters of the Arctic

Indian Art for Modern Living

- Subject: Native American Art

- Item # C3516R

- Date Published: 1941, Second Edition

- Size: Hardback with slipcover, 224 pages, 208 plates (8 in full color) SOLD

Publisher: