Subject: Zia Pueblo 19th Century Dough Bowl

Dough bowls apparently were not made at Zia Pueblo before the late 1700s, possibly because of the difficulty in firing such large vessels or perhaps because smaller bowls served the purpose and larger ones were not needed. The experience gained in making large storage jars for storage of dried foods and other necessities eventually paved the way for potters to experiment making dough bowls. The design elements on dough bowls have persisted almost without change since the first ones were made. This design was first developed on water jars during the San Pablo Polychrome period (1760-1820) and then used in dough bowls even into the present Zia Polychrome period.

This dough bowl is among the largest in diameter of most. At 19 inches (48.3 cm), it is just slightly smaller that one of the largest ones in the Smithsonian, which measures 50 cm in diameter. Assignment of a date of manufacture has been based on several design features defined by Harlow and Lanmon as belonging to certain periods of age. This bowl has been determined to fall in the 1850 to 1860 period based on their findings. The triangular pupils, one-armed cadre figure, black rim and lack of bird figures substantiate this date.

This is a classic mid-19th century dough bowl that is among the most desirable of all. The condition is extraordinary for one of this age. The black rim paint has been completely worn off from use, probably from the user's arms rubbing against the rim during preparation of bread dough. Other than that, the bowl is amazing in that the painted design is very visible.

Provenance: from a gentleman in Santa Fe

Recommended Reading: The Pottery of Zia Pueblo by Harlow and Lanmon

Subject: Zia Pueblo 19th Century Dough Bowl

Potter Unknown

Category: Historic

Origin: Zia Pueblo

Medium: clay, pigment

Size: 10-1/2" deep x 19" diameter

Item # 25610

Biography: Helen Naha (1922-1993) Feather Woman

Helen Naha (Feather Woman) and Joy Navasie (Frog Woman) were sisters-in-law. Helen Naha married Joy Navasie's brother, Archie Naha.

The two families lived on a large ranch just east of Keam's Canyon on the Hopi Reservation.

Helen was known for her stark black-on-white Hopi pottery early in her career and for exquisite polychrome pots in later times. Her hallmark is a feather.

Biography: Helen Naha (Feather Woman) [1922-1993]

Subject: Hopi Tall Polychrome Wedding Vase

Helen Naha (Feather Woman) and Joy Navasie (Frog Woman) were sisters-in-law. Helen Naha married Joy Navasie's brother, Archie Naha. The two families lived on a large ranch just east of Keam's Canyon on the Hopi Reservation. Helen was known for her stark black-on-white Hopi pottery early in her career and for exquisite polychrome pots in later times. Her hallmark is a feather.

Helen Naha (Feather Woman) and Joy Navasie (Frog Woman) were sisters-in-law. Helen Naha married Joy Navasie's brother, Archie Naha. The two families lived on a large ranch just east of Keam's Canyon on the Hopi Reservation. Helen was known for her stark black-on-white Hopi pottery early in her career and for exquisite polychrome pots in later times. Her hallmark is a feather.

This wedding vase is unusually tall and was slipped in white clay from top to bottom over which the artist applied the design in black, orange, and deep red. The design is a stylized version of a parrot, repeated on front and back of the vessel.

Condition: structurally in original condition with some minor scratches

Provenance: from a gentleman in Albuquerque

Recommended Reading: Hopi-Tewa Pottery: 500 Artist Biographies by Gregory and Angie Schaaf

Subject: Hopi Tall Polychrome Wedding Vase

Artist / Potter: Helen Naha (Feather Woman) [1922-1993]

Category: Contemporary

Origin: Hopi Pueblo

Medium: clay, pigment

Size: 14-3/4" tall x 7-3/8" diameter

Item # C3369C

Subject: Santa Clara Pueblo Black Carved Jar with Water Serpent

Most collectors are aware that Jennie Trammel made fewer pottery items than any of the other daughters of Margaret Tafoya. She had a full-time job away from the pueblo and had little time for making pottery. Interestingly, she was absolutely a phenomenal potter and produced the most beautiful carved wares of the 20th century.

This jar is typical of the exquisite work she produced. The carving of the clay around the Avanyu design is clean and of equal depth. The burnishing and firing were equally spectacularly accomplished. The jar is signed Jennie Trammel on the underside.

Condition: excellent condition with only a very few minor scratches.

Provenance: from a gentleman in Albuquerque

Recommended Reading: Born of Fire: The Pottery of Margaret Tafoya by Charles King

Subject: Santa Clara Pueblo Black Carved Jar with Water Serpent

Artist / Potter: Jennie Trammel (1929 -2010)

Category: Contemporary

Origin: Santa Clara Pueblo

Medium: clay

Size: 5-3/4" x 9-1/4" diameter

Item # C3369A

Subject: Northern New Mexico Landscape Painting

Summer storms over the mountains and hillsides of New Mexico are dramatic, exciting, and absolutely spectacular. Many New Mexico artists have captured the spectacle. Artists such as John Marin, Victor Higgins, Raymond Jonson and others have painted storms long in the past and now Navajo artist Tony Abeyta has done so. His storms are illustrated with billowing clouds that occupy half the painting with rain showers in isolated sections just as they do occur.

Tony Abeyta paints in a number of styles and in a variety of mediums, but these storm landscape scenes are a favorite of many collectors. Unfortunately, it is difficult to obtain one from the artist as he has gone on to other styles and does not like to regress to earlier works.

Framing: the painting is framed in a gold-leaf handmade frame by Gold Leaf Framemakers of Santa Fe.

Condition: new

Recommended Reading: 100 Artists of the Southwest by Douglas Bullis

Subject: Northern New Mexico Landscape Painting

Artist: Tony Abeyta (1965-present)

Category: Paintings

Origin: Diné - Navajo Nation

Medium: oil on board

Size: 15-3/4" x 19-1/2" image; 22" x 25-3/8" framed

Item # 25593

Biography: Ben Quintana (1923-1944) Ha-a-tee

It was a real tragedy that Ben Quintana (Ha-a-tee) of Cochiti Pueblo lost his life during World War II at only the age of 21 years. He was an outstanding artist and had a brilliant future in the art field. He was awarded the Silver Star posthumously for gallantry in action.

It was a real tragedy that Ben Quintana (Ha-a-tee) of Cochiti Pueblo lost his life during World War II at only the age of 21 years. He was an outstanding artist and had a brilliant future in the art field. He was awarded the Silver Star posthumously for gallantry in action.

Clara Lee Tanner, in her book, said of him:"This sensitive artist neglected no small detail in his painting. Colors employed by (him) are soft and pleasing throughout, and his treatment is direct and honest...Cochiti's greatest contributions, in the field of Southwestern Indian art have certainly come through Tonita Peña and her son, J. H. Herrera. Both have done important work in carrying on the traditional pueblo style of presentation....Had Ben Quintana lived, unquestionably, he would have equaled these two."

At the age of 15, Quintana won first prize over 80 contestants, of whom 7 were Indians, for a poster to be used in the Coronado Cuarto Centennial celebration. Later, he won first prize and $1000 in an American Magazine contest in which there were 52,587 entries. As testimony to his interest, he used the prize money to further his art education.

Biography: Ben Quintana (1923-1944) Ha-a-tee

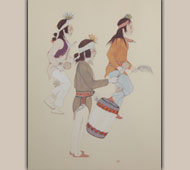

Subject: Cochiti Pueblo Original Painting of Dancers

At the age of 15, Quintana won first prize over 80 contestants, of whom 7 were Indians, for a poster to be used in the Coronado Cuarto Centennial celebration. Later, he won first prize and $1000 in an American Magazine contest in which there were 52,587 entries. As testimony to his interest, he used the prize money to further his art education. At age 21, he was a casualty of World War II.

At the age of 15, Quintana won first prize over 80 contestants, of whom 7 were Indians, for a poster to be used in the Coronado Cuarto Centennial celebration. Later, he won first prize and $1000 in an American Magazine contest in which there were 52,587 entries. As testimony to his interest, he used the prize money to further his art education. At age 21, he was a casualty of World War II.

As a teenage artist, one would expect paintings that were less than perfect; however, Quintana was well above average even at that age. His attention to detail is evident in all of his paintings and his treatment is direct and honest. His use of soft colors provides a pleasing and relaxing image. There is innocence to his paintings that might have been lost as he aged but we will never know.

Clara Lee Tanner, in her book, said of him: "This sensitive artist neglected no small detail in his painting. Colors employed by (him) are soft and pleasing throughout, and his treatment is direct and honest...Cochiti's greatest contributions, in the field of Southwestern Indian art have certainly come through Tonita Peña and her son, J. H. Herrera. Both have done important work in carrying on the traditional pueblo style of presentation....Had Ben Quintana lived, unquestionably, he would have equaled these two."

This painting, when compared to others we have had in the gallery, would appear to be a very early one of his. There is softness to the paint colors that became more intensified in his later works. Although, the span of his early to late works is only about 10 years because of his early death. He had an excellent command of facial features as illustrated by the three faces of these dance participants. He showed a lack of haste in his works and must have been a very patient person who did not rush to complete paintings but labored over each one until he was fully satisfied-a trait not expected of a teenage artist.

Condition: appears to be in excellent condition but has not been examined out of the frame. It appears that the mat board is acid-free indicating that the painting was recently re-framed. A simple silver wood frame was used.

Provenance: from a gentleman in Santa Fe.

Recommended Reading: Southwest Indian Painting: a Changing Art by Clara Lee Tanner

Subject: Cochiti Pueblo Original Painting of Dancers

Artist: Ben Quintana (1923-1944) Ha-a-tee

Category: Paintings

Origin: Cochiti Pueblo

Medium: watercolor on paper

Size: 13" x 10-1/4" image; 20-1/8" x 17-1/8" framed

Item # 25620

Subject: Original Painting "The Harvest Dancer" by Tommy Edward Montoya

Tommy Montoya's pastel drawings of traditional pueblo rites represent the blending of old and new that characterizes the work of young Native American artists. Authenticity is not something he studied; it is something he lived. As an active participant in pueblo ritual life, his works were created from memory. Montoya's dancers are not frozen in shape or time. They are, instead, the artist's personal expression of the color and motion of the moment. He liked to push his figures to the edges of the canvas or art board. That produced the feeling that they were being contained within borders and made them more dynamic and energetic. He was an extraordinary artist and has created an extraordinary drawing in this instance.

The painting is beautifully framed using all acid-free matting and silver tinted wood frame.

Provenance: From the estate of the artist. This pastel painting and the accompanying one (Item #25259) are two of the completed paintings remaining at the studio of Montoya when he passed away. He had just completed these two and was working on a third one.

Subject: Original Painting "The Harvest Dancer" by Tommy Edward Montoya

Artist: Tommy Edward Montoya (d.17 August 2009) Than Ts'áy Tas

Category: Paintings

Origin: Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo (San Juan)

Medium: Pastel

Size: 27" x 21" image; 40-1/2" x 33-1/2" framed

Item # 25260

Subject: Original Painting of a Jemez Pueblo Buffalo Dance

The plan for a painting studio at the Santa Fe Indian School had been four years in the making before it finally opened in the fall of 1932. Dorothy Dunn was in charge of the art department. It was in the second year of The Studio that Dorothy Dunn first mentioned Emeliano Yepa and she described him as painting pageantry. He was one of three students selected to paint murals in true fresco for The Studio and one of the residence halls. One of the mural paintings by Yepa was "A Summer Dance" (Corn Dance).

In the fourth year (1935-36), a Museum of New Mexico exhibit was organized to present to the public works by the students. Frederic H. Douglas's review of the show included the following statement "Much fine art will come from this area, with its strong tradition in painting. No.125 by E. Yepa, displays the work of a painter who clings, at least in his pictures, to a style seen in the first days of the movement. His conservatism is to be commended, for while progress is desirable, a brake is often useful."

An analysis of the works of all the students in the fifth year (1936-37) stated of Yepa "Emeliano Yepa had a somewhat stilted style which enhanced the formal patterns of ceremonial and small Jemez scenes he chose to paint. His brilliant palette brought animation and a note of daring to his balanced, conservative compositions."

The last mention of Yepa by Dorothy Dunn, in her book published in 1968, stated that "Emiliano Yepa, another fine artist of Jemez, is no longer living." There was no date given for his death. Jeanne Snodgrass, in her Biographical Directory published in 1968 lists the artist as Emilina rather than Emeliano but has no information regarding birth, death, or age. She states that the artist attended the Indian School from 1932 to 1937 and was included in a National Gallery of Art exhibit in Washington, DC in 1953.

This painting is of a Jemez Pueblo Buffalo Dance, a dance often seen during the fall and winter seasons. The costuming presented by Yepa is a very good representation of what one sees today at a Buffalo Dance. The men wear buffalo head covers and canvas skirts with a serpent encircling the mid-section and tin cones dangling from the hem section. The female wears a traditional pueblo dress and carries feathers in her hand. The painting is signed E. Yepa in lower right and on verso is rubber stamped The Studio U. S. Indian School, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Condition: very good condition with only a few minor flakes of missing paint

Provenance: sent to us by a gentleman from Colorado

Reference and Recommended Reading: American Indian Painting of the Southwest and Plains Areas by Dorothy Dunn

Subject: Original Painting of a Jemez Pueblo Buffalo Dance

Aritst: Emeliano Yepa (c.1920s- c.1950s)

Category: Paintings

Origin: Jemez Pueblo

Medium: watercolor

Size: 11-3/8" x 15-1/2" image; 16-3/4" x 20-3/4" framed

Item # C3355

Subject: Zuni Pueblo Five-strand Fetish Necklace

There were several artisans at Zuni Pueblo in the mid-1900s who became famous for their carvings of small bird and animal fetishes from a variety of stones and shells. The miniature fetishes were strung with hieshe and grouped in strings to form beautiful necklaces. Certainly two of the most famous were Leekya Deyuse (ca.1889 - 1966) and David Tsikewa (1915 - 1970). There were others and I am sure some knowledgeable collector or dealer could name them all and probably identify their works, but, unfortunately, I am not able to do so with this particular necklace.

There are five strands and each strand has 33 fetishes of birds and animals, for a total of 165 fetishes. Each strand is comprised of fetishes, hieshe and small turquoise cylinders. Silver cones tie the ends together and a handmade silver clasp completes the assembly. Each fetish carving is delicate and well executed. It is a strikingly beautiful necklace.

Condition: original condition

Provenance: from the personal collection of Margaret Gutierrez, Santa Clara Pueblo

Recommended Reading: Zuni Jewelry by Theda and Michael Bassman

Subject: Zuni Pueblo Five-strand Fetish Necklace

Unknown Maker

Category: Necklaces

Origin: Zuni Pueblo

Medium: variety of stones, shell

Size: 29" end to end

Item # C3371C

Subject: Bronze Sculpture of Kachin Mana Katsina "Emerging"

The kiva, which plays so vital a role in Hopi ceremonials, is a womb-like underground chamber from which the katsinas emerge. Hopis describe several cycles of global destruction and re-creation during two of which the chosen people were saved by living underground. The kiva acts as a reminder of these times and serves as a symbolic gateway to other realms.

The kiva, which plays so vital a role in Hopi ceremonials, is a womb-like underground chamber from which the katsinas emerge. Hopis describe several cycles of global destruction and re-creation during two of which the chosen people were saved by living underground. The kiva acts as a reminder of these times and serves as a symbolic gateway to other realms.

The Kachinmana is the feminine counterpart of the male katsina. The vision captured in this bronze is that of a strong figure emerging from the kiva to serve the Hopi people in their unending struggle for betterment.

This bronze, and others by the artist, are manifestations of an artistic eye and vision that spans two cultures, for Lowell was unusual in having spent many of his childhood years in the care of foster parents who raised him in a mainstream American home. Becoming Hopi meant for Lowell accepting a new reality and set of beliefs as well as coming to understand the traditions, ceremonies, languages and social customs implicit in his choice. Giving form to this historically-rich culture is a task Lowell set for himself with pleasure and excitement: what is ancient and inherently true to the Hopi people is newly rediscovered and revered through Lowell's dawning awareness of what it was to be Hopi.

Each form and figure tells a story as does the process Lowell employed in its creation. His images are inspired by Hopi beliefs and are "liberated" from cottonwood root-the Hopi traditional carving material-through Lowell's vision of what lies within. Although he could work faster in preparation for bronzing by using wax or clay, Lowell preferred to interact with wood, a material he respected for its life and character. The castings made from his carvings via the lost wax method retain that spirit. Even the grain of the original wood can be discerned in the finished bronze.

This bronze sculpture of Kachinmana Katsina was cast in 1982 by the lost wax method in an edition of 35 of which this is number 1.

Condition: original condition

Provenance: from the estate of a California family

Subject: Bronze Sculpture of Kachin Mana Katsina "Emerging"

Artist: Lowell Talashoma, Sr. (1950-2003)

Category: Bronze

Origin: Hopi Pueblo

Medium: bronze casting, wood pedestal

Size: 13-1/4" tall; 9-3/8" x 7" pedestal

Item # C3365A

Subject: Hopi Pueblo Polychrome Pottery Tile with Katsina Imagery

Tiles have been a popular collector's item for over a hundred years. The Hopi-Tewa potters have always been more prolific than the Rio Grande Pueblos in making them. Sadie Adams was very adept at making them and she made some of the largest tiles ever made. This tile is a good example of her large ones. It features a design that incorporates a portion of the Salakomana Katsina and its elaborate headdress.

This pottery tile is signed with one of her flower hallmarks: Sadie Adams (1905-1995) Flower Woman.

Subject: Hopi Pueblo Polychrome Pottery Tile with Katsina Imagery

Artist / Potter: Sadie Adams (1905-1995) Flower Woman

Category: Contemporary

Origin: Hopi Pueblo

Medium: clay, pigment

Size: 8-3/4" x 6-1/2"

Item # 25619

Biography: Sadie Adams (1905-1995) Flower Woman

Sadie Adams' Hopi name is Flower Girl (Flower Woman) and she signed her pottery with a flower symbol. She was a Hopi-Tewa of the Kachina/Parrot Clans and lived in the Tewa village at First Mesa on the reservation.

She was recognized by collectors and her contemporaries as an outstanding potter. She had a long, successful career making and selling pottery on the reservation and supported her family in this manner following the death of her husband. She supported her family solely from sales of her pottery, even sending her daughter to nursing school.

She usually signed her pieces using one of the following three flower hallmarks (see images):

She was very versatile in the pottery she made-jars bowls, lamps, tiles, cookie jars, plates, cups and saucers-that it is no wonder that she has such large collector enthusiasts today. She made something for everybody's budget and desires.

Biography: Sadie Adams (1905-1995) Flower Woman

Subject: Hopi Second Mesa Plaque

Coiled basketry of this type is made exclusively in Second Mesa villages on the Hopi Reservation. Each stitch of a coil is interlocked into the adjoining stitch of the previous coil. An awl is used to facilitate this. This basket probably took the weaver more than two months to complete the weaving process alone, not counting the months of gathering materials, drying the yucca leaves, then splitting them to a thin, consistent width, dying some of them, and preparing the grass for the foundation. I have watched a number of women at Second Mesa villages make baskets over the years, and I am in awe of their patience and fortitude.

Coiled basketry of this type is made exclusively in Second Mesa villages on the Hopi Reservation. Each stitch of a coil is interlocked into the adjoining stitch of the previous coil. An awl is used to facilitate this. This basket probably took the weaver more than two months to complete the weaving process alone, not counting the months of gathering materials, drying the yucca leaves, then splitting them to a thin, consistent width, dying some of them, and preparing the grass for the foundation. I have watched a number of women at Second Mesa villages make baskets over the years, and I am in awe of their patience and fortitude.

The design of this plaque is very subtlety divided into four quadrants by a very faint green pigment applied over the yucca, a technique I have not seen before on Hopi basketry. The two large designs with red appear to possibly represent an unmarried Hopi girl's hair whorl, but this is speculation on our part. It is conceivable that this was used in a ceremonial function relating to a young Hopi female.

Condition: very slight fading between front and back, otherwise in excellent condition

Provenance: from the collection of a member of the Balcomb family

Recommended Reading: Hopi Basket Weaving, Artistry in Natural Fibers, by Helga Teiwes.

Subject: Hopi Second Mesa Plaque

Weaver Unknown

Category: Trays and Plaques

Origin: Hopi Pueblo

Medium: grasses, yucca, dyes

Size: 12-3/4" diameter x 2-1/8" deep

Item # C3368D

Subject: Hopi Polychrome Bowl by Nampeyo, circa 1910-1920

This large open bowl is attributed to the great Hopi potter, Nampeyo of Hano, based on similarities to many documented works of hers. The following quotation is from a Letter of Attribution which accompanies the purchase of the bowl:

This large open bowl is attributed to the great Hopi potter, Nampeyo of Hano, based on similarities to many documented works of hers. The following quotation is from a Letter of Attribution which accompanies the purchase of the bowl:

"The molding is classic Nampeyo: the rim has the characteristic extra coil, the bottom is perfectly rounded, not flattened, and shows the long stroke marks indicative of Nampeyo's polishing. Overall, the bowl exhibits the solid symmetrical shape and mature molding that we associate with Nampeyo, and for which there are many documented examples. The clay paste also shows small flakes of mica commonly seen in Nampeyo's pottery.

"The painted design is classic Nampeyo, and in fact, there is a similar bowl also by Nampeyo in the permanent collection of the Milwaukee Public Museum that is the match to this bowl. Both bowls show the classic heavy black double framing lines around the elaborate abstracted bird design in the center. Under a polished red sky band, the spirit bird dangles its beauty to please the Hopi deities. At the top of the design, we see the classic triangular accordion shapes of the kachina's lightening frame ending in a large bird's wing, a frequent Nampeyo design element. Beneath, we see the bird's body with its interior nicely abstracted, while three tail feathers complete the vertical design. To the sides, elaborate feathers are presented. Interestingly, the classic swirl design that Nampeyo originally borrowed from the prehistoric Sikyatki potters and which dominated much of her early work is here reduced almost to an afterthought and used only as a small portion of her design on the right side of the bird. But it is this shift of focus that dates this piece to Nampeyo's mature period, from 1910 to 1920, when she has integrated the great Sikyatki designs into her work and is producing fluid masterful painting from her own genius, surpassing her original models." Steve Elmore Indian Art

Condition: good condition with no repair or restoration but with expected amount of wear

Provenance: previously from an estate in Oregon, now from a gentleman in Connecticut.

Recommended Reading: Canvas of Clay: Seven Centuries of Hopi Ceramic Art by Edwin L. Wade and Allan Cooke

Subject: Hopi Polychrome Bowl by Nampeyo, circa 1910-1920

Artist / Potter: Nampeyo of Hano (1857-1942)

Category: Historic

Origin: Hopi Pueblo

Medium: clay, pigment

Size: 3-1/8" deep x 11" diameter

Item # 25618

Biography: Nampeyo of Hano (1857-1942)

Nampeyo of Hano was the first pueblo woman to gain recognition for her pottery. She lived and worked at a time when putting one's name on the vessel was not done, so little, if any, of her pottery is signed. She spent a large part of her productive life supplying pottery to the Fred Harvey Company for re-sale, so documentation of her work is well established.

Note: Nampeyo's birth date has been stated to be either 1857 or 1858 by noted photographer W. H. Jackson who photographed her in 1875 at the time he said she was 17 or 18 years of age. (Plateau, A Quarterly. October 1951, Volume 24, Number 2, page 92).

Biography: Nampeyo of Hano (1857-1942)

Subject: Zuni Pueblo Polychrome Jar by Tsayutitsa, c.1935

Tsayutitsa, also known as Mrs. Milam's mother, was certainly one of the finest potters of the first half of the 20th century from Zuni Pueblo. She is known for her superbly formed jars and meticulous painting of designs. Her pottery was not signed but it is unmistakably identified by the superb craftsmanship. This jar is without a doubt the work of Tsayutitsa.

Dr. Edwin Wade has examined this jar and prepared a document of description and authentication, which we reprint below:

A ZUNI POLYCHROME JAR BY TSAYUTITSA C. 1935

"Zuni stylistic conventions may appear broadly consistent over time. However, prior to the mid-19th century, the potters of the Kiapkwa and earlier Ashiwi traditions (forerunners of modern Zuni) were notably experimental. These earlier times witnessed increased pan-Puebloan communication and travel and through this widened contact new ideas flowed.

"Zuni stylistic conventions may appear broadly consistent over time. However, prior to the mid-19th century, the potters of the Kiapkwa and earlier Ashiwi traditions (forerunners of modern Zuni) were notably experimental. These earlier times witnessed increased pan-Puebloan communication and travel and through this widened contact new ideas flowed.

"The second half of the 19th century, with the coming of Anglo settlers and a host of new diseases, was difficult for all the Pueblos, but particularly for the remote communities of Hopi and Zuni. The harshness of these times likely contributed to an aesthetic and compositional entrenchment of Zuni. Yet, as attested to by early anthropologists, conservatism may also spring from a group psyche in which difference and the unusual are approached with distrust and aversion. The more that Zuni became 'stay at home' the greater their preference for a limited number of design compositions and layouts such as 'deer jars' and hachured 'rain birds' and rectangular geometrics.

"There was assuredly a positive side to this conservatism, as evidenced in this beautifully shaped and painted jar. The flashiness of innovation can obscure degrees of artistic perfectionism and technical excellence. Within Zuni ceramics, it's impossible to hide lack of artistic skill behind the glamour of the new and unusual.

"The deer pot pictured above is composed of four vertical under- to upper-body design fields, two of which have three horizontally stacked panels containing housed black deer separated by a band of serially repeated red birds, offset by two elongated rectangular panels which each contain one arabesque Spanish-derived motif. This particular composition first arose in the late 1860s to early 1870s and has been a hallmark of Zuni art ever since.

"Comparing such vessels from their inception to the present day easily separates the vast majority of rank and file competent talent from that of the very few geniuses. This jar, made in 1935 by the master Zuni potter Tsayutitsa (1870s - 1959), is one of those few masterpieces.

"By the turn of the 20th century, Zuni pottery was in decline. Certain scholars maintain that only three or so potters of that time were capable of matching the greatness of their 19th century counterparts. And of those few, Tsayutitsa was unquestionably the best. She specialized in oversized storage jars, which likely was a result of her working for the Indian trader C. G. Wallace. Wallace was widely known for supplying museums and advanced collectors with the finest of ancient and modern Zuni art.

"Her vessels are characterized by bulbous, bubble-like bodies with a sharp upperbody (sic) flexure from which a short conical neck arises. A heavy white kaolin slip was applied to the clay body and meticulously stone polished. The result is a creamy, lustrous finish that is finely crazed. The vessels are thin-walled and the painting is richly-colored, extremely precise, and refined.

"Notably, in addition to all these traits, this jar displays one of the earliest known evidences of an artist's 'signature' on Pueblo pottery at a time well before this became common practice. This jar is inscribed on the interior of the upper shoulder as follows: 'ZUNI 1935 N. M.' These words, almost certainly written by the potter, are executed in child-like, large block capital letters and are rendered in the exact same red paint used by the artist in painting the exterior design of the jar. UV light examination reveals that the inscription was applied after the vessel was fired. It is possible that this 'signature' could have been added at the behest of Tsayutitsa's longtime patron, trader C. G. Wallace, to mark the jar for participation in or a competition judging at an event such as the nearby Gallup Ceremonial. In any event, this marvelous inscription is unique in my experience and is another testament to the special and compelling nature of this vessel.

"In my estimate, Tsayutitsa is one of the master Pueblo potters along with Nampeyo of Hopi and Maria Martinez of San Ildefonso. I am not alone in this assessment as reflected in the comments of Robert Gallegos in describing a Tsayutitsa jar for sale at Skinner's auction (Sale 2376 - lot 340) 'Tsayutitsa was a great potter and a great painter, making her in my opinion, one of the best, if not the best potter of all time.'

"Museums throughout the United States are now combing their collections with new expertise in the hope of finding a Tsayutitsa within their holdings. When one is found it is rushed to the exhibition gallery. To personally own one of her vessels is a rare privilege as she is deserving of a hallowed place within any collection."

/// Signature ///

Edwin L. Wade, Ph.D.

Condition: excellent condition

Provenance: from a gentleman in Santa Fe

Recommended Reading: The Pottery of Zuni Pueblo by Harlow and Lanmon

Subject: Zuni Pueblo Polychrome Jar by Tsayutitsa, c.1935

Artist / Potter: Tsayutitsa (1870s - 1959)

Category: Historic

Origin: Zuni Pueblo

Medium: clay, pigment

Size: 8-7/8" tall x 11-3/8" diameter

Item # 25612

Biography: Tonita Vigil Peña (1893-1949) Quah Ah

Tonita Peña, whose Indian name was Quah Ah, was born in 1893 in the tiny New Mexico pueblo of San Ildefonso on the Rio Grande, just north of Santa Fe. At about the age of 12, her mother passed away and her father, unable to raise her and tend his fields and pueblo responsibilities, took her to live with her aunt and uncle at Cochiti Pueblo, where she spent the remainder of her life.

Tonita was the only woman in the group of talented early pueblo artists referred to as The San Ildefonso Self-Taught Group, which included such noted artists as Julian Martinez, Alfonso Roybal, Abel Sanchez, Crecencio Martinez, and Encarnación Peña.

By the time Tonita was 25 years old, she was a successful easel artist, and her work was being shown in museum exhibitions and in commercial art galleries in Santa Fe and Albuquerque. She painted what she knew best — scenes of life at the pueblo — mostly ceremonial dances and everyday events. She is still considered one of the best female Indian artists of all time.

Tonita was very ingenious in the manner in which she signed her paintings. After extensive and careful study of over one hundred of her paintings, it is possible to date a number of her paintings, within reason, by the manner in which they were signed.

Joe Herrera has stated that when his mother first started painting she signed all of her paintings with her Indian name

![]()

This lasted until sometime in 1915. A variation of this signature occurred shortly before or at the time Tonita became pregnant with her second son, Joe H. Herrera, probably in 1917 or 1918. She then modified

![]()

and used the signature

![]()

separating and capitalizing the H in her first name, in honor of her second husband, Herrera. This was used until the death of Felipe Herrera in 1920. These signatures are rare as Tonita did not paint much at that time.

She began to use her baptismal name, ![]()

sometimes alone, sometimes with the pueblo name, and sometimes embellished with a decorative motif. She continued using this until she met Epitacio Arquero in about 1921.

She then used both names in her signatures, one name above the other:

A very few of Tonita's works painted in 1922 and 1923 were signed

![]()

in honor of her husband, Epitacio Arquero. These signatures are also quite rare.

In the early 1930s Tonita began using small combinations of cloud, rain, and storm motifs in conjunction with her name or names, sometimes using the names with the motifs. These became more intricate and complicated in design as time went on, and were used until her death. Remarkably, Tonita never repeated the same design, but always used a different combination on each painting.

Excerpted from: Tonita Peña by Samuel L. Gray, 1990. Avanyu Publishing (Alexander E. Anthony, Jr.), Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Subject: Original Painting of a Pueblo Corn Dancer, circa 1921

This original painting by Tonita Peña (Quah Ah) of San Ildefonso Pueblo was probably painted in 1921, this being based on the dual signature of her Native name and baptismal name.

This original painting by Tonita Peña (Quah Ah) of San Ildefonso Pueblo was probably painted in 1921, this being based on the dual signature of her Native name and baptismal name.

The image depicts a male pueblo Corn Dancer in the traditional style with no ground plane and no background. In her paintings of dancers such as this she was able to make her dancers appear in motion rather than fixed in time. He is beautifully rendered in all the splendor of his dance clothing and body paint. Tonita was very good and presenting the finest detail of her dance figures.

Joe Herrera has stated that when his mother first started painting she signed all of her paintings with her Indian name. This lasted until sometime in 1915. A variation of this signature occurred shortly before or at the time Tonita became pregnant with her second son, Joe H. Herrera, probably in 1917 or 1918. She then modified and used the signature separating and capitalizing the H in her first name, in honor of her second husband, Herrera. This was used until the death of Felipe Herrera in 1920. Around 1921, she started using both of her names, one above the other.

Condition: appears to be in good condition with a slight browning of the paper

Provenance: from the collection of a Santa Fe family

Recommended Reading: Tonita Peña by Samuel L. Gray

Subject: Original Painting of a Pueblo Corn Dancer, circa 1921

Artist: Tonita Vigil Peña (1893-1949) Quah Ah

Category: Paintings

Origin: San Ildefonso Pueblo

Medium: gouache

Size: 7-1/2" image x 5-1/2" image; 11-3/4" x 9-3/4" framed

Item # C3374

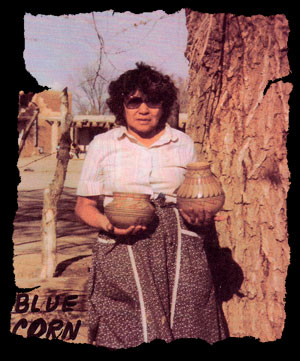

Biography: Crucita Gonzales Calabaza (1921-1999) Blue Corn

Blue Corn was born in San Ildefonso around 1923 and was encouraged by her grandmother, at an early age, to "forget school and become a potter." She did attend school at the pueblo and later at the Santa Fe Indian School, however. At age 20, she married Santiago, a Kewa Pueblo (Santo Domingo) silversmith. During the 1940s, she worked at Los Alamos as a housecleaner for J. Robert Oppenheimer. Shortly after World War II, she took up pottery making and found her calling.

Blue Corn was born in San Ildefonso around 1923 and was encouraged by her grandmother, at an early age, to "forget school and become a potter." She did attend school at the pueblo and later at the Santa Fe Indian School, however. At age 20, she married Santiago, a Kewa Pueblo (Santo Domingo) silversmith. During the 1940s, she worked at Los Alamos as a housecleaner for J. Robert Oppenheimer. Shortly after World War II, she took up pottery making and found her calling.

Blue Corn is famous for re-introducing San Ildefonso polychrome wares which had become a lost product after the blackware of Maria and Julian had become in such demand in the 1920s. She also made blackware and redware but is most often associated with polychrome wares.

Blue Corn passed away on May 3rd, 1999.

Credit: Photograph images courtesy of Garry and Susan Zens. Copyright Adobe Gallery, all rights reserved.

![Santa Clara Pueblo Black Carved Jar with Water Serpent Most collectors are aware that Jennie Trammel made fewer pottery items than any of the other daughters of Margaret Tafoya. She had a full-time job away from the pueblo and had little time for making pottery. Interestingly, she was absolutely a phenomenal potter and produced the most beautiful carved wares of the 20th century. This jar is typical of the exquisite work she produced. The carving of the clay around the Avanyu design is clean and of equal depth. The burnishing and firing were equally spectacularly accomplished. The jar is signed Jennie Trammel on the underside. Condition: excellent condition with only a very few minor scratches. Provenance: from a gentleman in Albuquerque Recommended Reading: Born of Fire: The Pottery of Margaret Tafoya [SOLD] by Charles King](https://www.adobegallery.com/uploads/C3369A-carved.jpg)