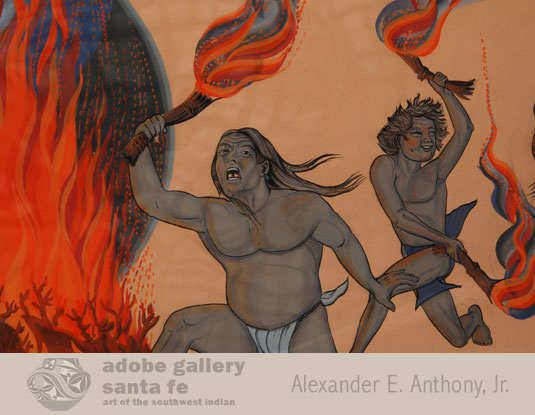

Quincy Tahoma Depiction of Diné Fire Dance of the Mountain Chant [SOLD]

+ Add to my watchlist Forward to Friend

- Category: Paintings

- Origin: Diné of the Navajo Nation

- Medium: casein

- Size:

18” x 28-1/2” image;

31-1/4” x 40-3/8” framed - Item # C3878 SOLD

The Navajo Fire Dance is a public dance performed at the end of the nine-day Mountain Chant. To start the dance, many young men drag great trees for a central fire, which rapidly turns into fierce flaring, crackling, and roaring heat. When it becomes its hottest, suddenly the loud burring call of the fire-dancers fills the air.

Quincy Tahoma (1917-1956) Water Edge - Near Water has presented the Fire Dance in a most accurate manner as performed by the group of young men, always young men, because of the demanding energy required. To appreciate the intensity of the Fire Dance, we rely on a description by Dr. Washington Matthews who attended such a dance in the 19th century.

The following is his description of the Fire Dance as he witnessed it.

"The men, racing in a circle round the fire, close to the unbearable heat, whooped like demons and beat their own bodies and each other's with the flaming brands. One man beat the bare back in front of him until it slipped away. Then he flared his brand over his own back, showering sparks, he straddled it as he ran, he turned and threw its flames over the man who followed him. They washed each other's backs with flame. They leaped so close to the fire that their bare feet seemed to be treading on live coals. The figures, following each his own devices, together made a painting such as Doré might have done for Dante's Inferno: pale inhuman figures, capering in the firelight, bathed in the red glow and the showers of orange sparks, always calling that queer suggestion of flickering flame. It seemed to last a long time; actually, until the cedar brands were well burned out. Then each man dropped his smoldering bark and, still trilling loudly, ran out of the corral. Intense, brilliant, savage.

"As the dancers left, spectators swarmed in to pick up bits of the burned cedar, sure protection against danger of fire for the year to come. By this time the east was showing white, that comfortless early morning light which makes everyone ghastly. Even brown Navajo faces looked gray. White people appeared as at the end of a long illness or a terrific debauch. The fire was burning low again, but nobody built it up. Then the chief medicine-man came in. He had not been seen all night, his task having been to sit in the hogan, chanting. Now he entered, accompanied by his assistants, and chanted while they scattered water on the fire at the four ceremonial points. Then young men tore gaps in the circle of branches, one opening toward each direction. As the medicine-man went back to the hogan, they demolished the whole corral, leaving the branches on the ground. Day was full by that time, and the circle of prostrate branches was like a stage with all the scenery removed and the curtains rolled up. The only important matter seemed breakfast, especially coffee."

Tahoma, who normally painted muscular beautiful young men, chose to present these men in a more realistic manner with less than the perfect body. One young man is thin and not muscular, another is fatter with his stomach hanging over his belt. The men all have grey bodies, a result of smearing ashes over themselves. The faces of the young men show their seriousness in what they are doing. They are not playing around but are seriously carrying out the function of the dance.

The intense color in the painting comes from the fire the men are brandishing and the bonfire behind them. The powerful red fire and the shades of blue and grey smoke deeply impresses the viewer with the intensity of the heat. It makes one think “how do they do it, how do they contend with the heat?”

Tahoma was a master painter, able to express, with paint on paper, an event that is from the past, yet as modern as an event that could have been choreographed recently. Tahoma won high praise from academically trained artists of note and an admiring public. His paintings were in demand when he was producing them and even more so now that he has been gone for over 60 years. Even those who do not appreciate Native American art as something they wish to collect, they do appreciate the technical expertise of the artists involved, and Tahoma is high on the list of those receiving praise.

The painting is signed in lower right with the artist’s name and a cartouche showing the next scene. It is dated 1953.

Condition: this Quincy Tahoma Depiction of Diné Fire Dance of the Mountain Chant appears to be in original condition and has just been framed using archival materials and a wood frame.

Provenance: from a gentleman in Santa Fe

Recommended Reading: Quincy Tahoma, The Life and Legacy of a Navajo Artist by Charnell Havens, et al

Realtive Links: Quincy Tahoma, Navajo Reservation, Taos, San Juan, San Ildefonso, Painting

- Category: Paintings

- Origin: Diné of the Navajo Nation

- Medium: casein

- Size:

18” x 28-1/2” image;

31-1/4” x 40-3/8” framed - Item # C3878 SOLD