Polychrome on Red Canteen by Nampeyo and Annie, c.1905 [SOLD]

+ Add to my watchlist Forward to Friend

- Category: Historic

- Origin: Hopi Pueblo, Hopituh Shi-nu-mu

- Medium: clay, pigments

- Size: 9-1/4” tall x 8” wide x 5-3/4” deep

- Item # C3273C SOLD

The following information is from a letter of attribution by Edwin L. Wade, PhD

Historically, Hopi ceramics took a variety of forms—water jars, storage jars, cups, ladles, dippers, bowls, figurines, pipes, tiles, ceremonial items, and canteens. Canteens would prove one of the most difficult forms to master, and among the best of their makers, as attested to in this vessel, were Nampeyo and her daughter Annie.

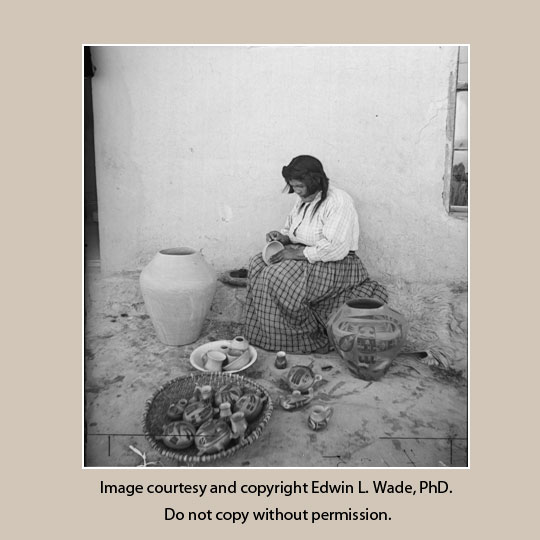

We know that Nampeyo was producing canteens as early as the 1890s, but it was the cash incentive of the Fred Harvey curio trade that pushed canteen production, along with vessel miniaturization, into an accelerated mode. Nevertheless, there was never a slacking of artistic precision and aesthetic innovation on the part of these two outstanding potters, and in many cases the domed surface of these water bottles further challenged their compositional genius, as documented in a 1905 photograph.

The two potters worked so long and closely together that it remains difficult to precisely distinguish their separate hands. Further complicating this is the tendency of early tourists and museum curators to ignore the contribution of Annie and give sole credit to Nampeyo. Yet, public and private collections contain enough pieces documented as Annie's to allow some generalizations about her design and compositional preferences. All of those are seen in this beautifully conceived canteen.

Nampeyo experimented with red ware but Annie truly favored it. She also accentuated her compositions with the addition of a thick white kaolin pigment, as seen in the central Maltese cross of this vessel. The construction of the cross is true to the earliest 17th century Hopi use of this Spanish motif first seen on the painted wainscoting in the interior of the Franciscan mission of San Bernardo Awatube. To see the cross, non-Hopi viewers must reverse their perception and see the white as the positive design and the red lancets as negative. Just look towards the center and slightly unfocus your eyes and then suddenly four triangular blades make a flanged square. Projecting from two of its sides are bold crosshatched crescents with white feather tips. The above and below sides are capped by a serrated or stepped pyramid with internal frets.

When Annie was painting as Annie and not as Nampeyo, the compositions, as with this vessel, tended to be simpler and bolder, with an inherent sense of dynamic motion. Here the curved feathers are like spinning rotor blades on a saw or helicopter locked into a central gear. It is an extremely effective and delightful composition for the dome of a canteen.

There is a delicious richness to the red slipped clay and vivid black and white pigments. Owing to its meticulous polishing, the vessel seems almost moist—and what more appropriate surface could there be for a water bottle in the arid mesa country of Hopi.

Signed Edwin L Wade

Condition: exceptional condition for a vessel that is over 100 years old

Provenance: from the collection of John W. Barry. Published in American Indian Pottery by John Barry, plate 148, 1984

Recommended Reading: American Indian Pottery by John Barry

- Category: Historic

- Origin: Hopi Pueblo, Hopituh Shi-nu-mu

- Medium: clay, pigments

- Size: 9-1/4” tall x 8” wide x 5-3/4” deep

- Item # C3273C SOLD